As soon as SDOT announced the Fauntleroy Way road work – repaving, rebuilding, “rechannelizing” – was almost done, the questions began, including, why isn’t it all blacktop? We arranged to chat and stroll with SDOT project manager Jessica Murphy to get some answers as the work wrapped up.

(looking north across Fauntleroy at 42nd SW, foreground in shadows)

By Tracy Record

West Seattle Blog editor

Now that the end of the Fauntleroy Way repaving/rebuilding work between Edmunds and Holly is here – and so are the “rechannelization” lines – new questions have surfaced (as have new features).

View Larger Map

SDOT explained along the way that the stretch of Fauntleroy covered in this $3+ million dollar project (first revealed here last October, with the lane-reconfiguration “rechannelization” plan first made public in November) is a three-section road: Concrete on each side, asphalt down the middle where a gap once existed with thoughts a streetcar track would be built.

When I sat down with SDOT’s Jessica Murphy – a West Seattleite, by the way – at a Morgan Junction coffee shop last week to talk about the project, she brought along a few more specifics about that history – the east section of the road was built in 1927; the west, 1949; and the last major work on the road, including the section where the streetcar track never got built, was 1984.

The roots of what you see today – some spots that are blacktop adjoining some spots that are not – are in 1984, when sections of cement roadway were overlaid in asphalt. It’s particularly noticeable stretching west from Fauntleroy/Graham (map):

Murphy says the asphalt overlay is not considered necessary any more – the asphalt doesn’t add any “structural benefit,” but does add cost — putting it over the west stretch, for example, would have cost $200,000 more, but “added no lifespan.”

That said, two points are worth noting: Once a road is overlaid with asphalt, she says, it needs to stay that way, in no small part because the utilities and other features are built to work with the road at that height (generally two inches over the concrete road base). Also, perhaps most notably, even though your eyes would tell you otherwise, nothing has changed in this project – the section where you see asphalt now is where there was asphalt before – the section where you don’t, didn’t have it. Over time, the two-tone look will soften, she says, adding that the black marks on some of the concrete, blamed on trucks driving over the “tack,” will go away too.

Asphalt itself is less expensive than concrete, and Murphy says it was chosen for the complete replacement of the center of Fauntleroy Way because they usually reserve new concrete-road construction for areas of heavy traffic loads like buses; here, she says, the “full-depth asphalt” center section of Fauntleroy — 10 inches of asphalt and about half a foot of crushed rock — should last 30 years.

Other questions have focused on why some parts — “panels” — in the road’s concrete sections were replaced and not others. “Most concrete is designed for a 40-year lifespan, but the weather here is relatively mild, and doesn’t go through a freeze/thaw cycle like the east coast.” Result, she says, some of the “panels” – the sections of concrete roadway – were in good shape and didn’t need to be replaced.

If you see cracks in panels, that does NOT mean it should have been replaced but wasn’t. As Murphy explains it, “Just because it has a crack doesn’t mean it’s failed. Technology has evolved. We now know some of the panel sizes used were too large. They cracked where they ‘wanted’ to have a joint” – the line where two panels connect.”

As we strolled northeast on Fauntleroy, she pointed out one such example on the south side of the street:

If you want to compare that to a cracked panel that IS failing and will need to be replaced, Murphy pointed this one out on the small section of 42nd SW between Morgan and Fauntleroy (map):

The visual difference in the concrete pavement surface, by the way, between old concrete and new concrete, has to do with the type of “aggregate” – stones – that’s used; Murphy says that while the aggregate often could be seen as stones in their original shape (still the case in so many stretches of old sidewalk as well), the rock is crushed before being mixed in nowadays.

Regarding the old concrete, we asked: If some of the panels that weren’t replaced are technically beyond their basic life span already, how long is the partly rebuilt road supposed to last before it needs more major work?

“This is a maintenance project, geared to a 15- to 20-year lifespan” – so theoretically, you won’t see another project like this, along this road, any sooner than the 2020s, but SDOT believes even the older panels that were left in place will last that long.

Murphy and Marybeth Turner from SDOT — who helps us find answers to many West Seattle road questions day in and day out and joined us partway through the conversation — said they’ve also been asked why the California/Fauntleroy intersection itself wasn’t rebuilt or resurfaced. Murphy says that section was repaved more recently than the rest of the Fauntleroy stretch involved in the current project, and “will be in cycle to do along with the rest of (southern) California … which is an ‘identified paving need’ but not currently scheduled.”

A significant stretch of northern California SW, you’ll recall, was repaved back in 2007-08; while it’s all asphalt-topped, under the surface it’s the same three-part structure as Fauntleroy Way is now – two concrete sides with asphalt in the middle.

But as this one is wrapped up, there are a few extra touches you might not have recognized would be part of the plan. For one, as originally revealed in x, the repaving has stretched westward to SW Holly (map), made possible when the bids came in lower than expected. “We were very excited to go (that far),” Murphy notes.

She also called our attention to some work that was being done the day we spoke:

That crew was putting in curb bulbs by the Fairmount Springs “island,” to facilitate a Fauntleroy Way crosswalk at Juneau (map), and also to make sure people don’t “fly,” as Murphy put it, down 40th; she says the end configuration will be a lot like nearby 39th SW.

Then there’s the concrete work along Fauntleroy on the north side of Zeek’s Pizza. Since the future RapidRide bus service is supposed to have a stop there, that section of the road now has a concrete section to withstand the weight of the buses; since RapidRide will follow California, not Fauntleroy, Murphy says that’s the only section of this project that “overlaid” the RR route.

As this wraps up, and then 16th SW (which we updated last week), you are not likely to see major SDOT work in West Seattle for at least a year — we asked Murphy if next year’s SDOT paving list includes major West Seattle projects; in a word, no.

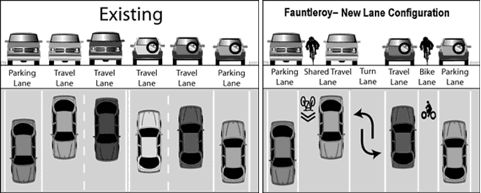

So from here, once the final signs and barriers are gone, it’s up to drivers to decide if the rechannelizing of Fauntleroy done along with the paving is working for them – here’s a refresher on how it changed:

In public discussions before the decision was made late last year, SDOT reps reiterated that the road could be restriped if the new configuration turned out to be a disaster. (The work done to rebuild and repave will withstand any configuration, according to Jessica Murphy.) You can provide feedback through contact information at the bottom of this SDOT page.

| 34 COMMENTS