By Tracy Record

West Seattle Blog editor

This past Saturday’s open house at Westside Neighbors Shelter in The Triangle turned out to be a two-part event – open house for information about the shelter, open mic for questions and complaints about it.

The latter came from people in neighborhood homes and businesses who say the shelter – the only facility of its kind in West Seattle – has become a “magnet” for street disorder. Shelter founder/manager Keith Hughes countered that what people are seeing in the area exists elsewhere in this city and many others. More on the discussion later, but first:

Hughes explained that the shelter began inside the American Legion Post 160 hall in 2019 “by accident, “I didn’t intend to start a shelter, I didn’t expect to run it for seven years.” One morning he came in to do paperwork as Post 160 commander and discovered people sleeping outside the door; he invited them in: “Come in and warm up and have some coffee,” which he said is “what we’re still saying.” Now they serve a full breakfast to upwardsof 30 people, with a hot shower and clothing if they need it. Before the presentation he showed us the new dining area they’d carved out of some space at the hall:

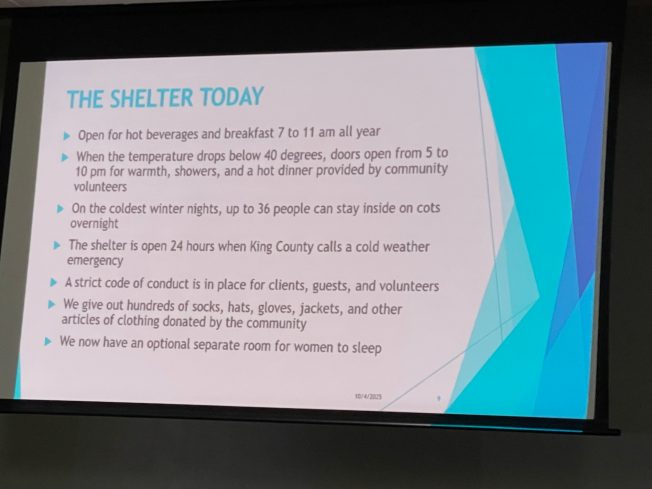

The presentation and Q&A period was moderated by volunteer and board member Laurie Utterback, who explained that the only paid staff are security guards hired when overnight season starts. “We’re all committed to helping these people who have nowhere else to go.” Hughes said the shelter, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, has the mission “to serve our community with compassion, respect, determination.” It’s not open overnight until the truly cold weather arrives, typically in November. They started with capacity for about a dozen people; that has tripled over the years with the help of some other additions like a washer/dryer and third bathroom.

During overnight-operations season, they open at 5 pm for dinner, then when breakfast is done at 11 in the morning, the shelter closes for the day. “So there’s still a period 11 am to 5 pm when people are out on the streets, in the cold.”

They have case managers now on site five mornings a week, from a private organization, to help get people into temporary and then permanent housing. Hughes said they also have doctors from the community volunteering at the shelter two days a month. But overall, the shelter remains without regular government support; he’s working on registering it with the King County Regional Homelessness Authority, a months-long process, and has just hit one milestone, a Master Service Agreement, which could at least make the shelter eligible for some reimbursement after cold-weather emergencies.

Otherwise, he said, the shelter’s work is funded “by hundreds of donors and a few private foundations.” Hughes stressed he’s “not a professional fundraiser” but others have been organizing benefits, such as a November 8th benefit concert by the Boeing Employees Choir. And he concluded by noting that the shelter benefits not only from donations of food, clothing, money, etc., but also by word of mouth – people tell others about it, and “these second- and third-hand connections are where we’ve been able to make some headway.”

Introduced next was a former shelter guest who said she had spent several months there. “I came here on my birthday, December 1st, last year, saw a sign in a bathroom in a library.” She had been sleeping in her car. At the shelter, they had no bed for her but she slept on a mat on a floor, and said that was vastly better than in her car. She started to do work to help out at the shelter, like laundry. When it closed for the season “I still stayed in the backroom and was helping with security stuff and ODs – I used to be an MP so it was a natural step for me.” Now a case manager has helped her get an apartment in Sand Point, “a studio and a half,” and she’s been getting settled.

That was followed by Q&A. There was one overarching question asked by multiple people identifying themselves as either nearby residents or owners/clients of nearby businesses including day care/preschools: What action will Hughes take regarding street disorder outside the shelter that “spills into the community around” it?

To the first person who asked, wondering about a “road map” to deal with problems outside the shelter, Hughes countered, “How does this differ from any other community?” regarding troubled people on the street.

“That’s a good question,” the attendee acknowledged, while saying it didn’t negate her safety concerns.

Hughes went on: “This is one small part of the city of Seattle. The city has a problem. We all know that. Do I have a road map to fix the problem? Does the mayor? No. We’re on our own here and we’re doing the best we can.” He said they’d had community meetings and that the shelter was operating “differently … better” but ultimately, he said, dealing with troublemakers would take “money … security guards get $50 an hour … The only way to satisfy people … is to hire more security guards. My daytime helpers and I cannot babysit 50 people.”

He also suggested the surrounding area wasn’t as trashed as people mentioned, noting a Chamber of Commerce-organized cleanup a few weeks ago: “For six blocks around, we picked up one bag of trash. Not one single needle, no feces, a few pieces of (scorched) foil – one bag in six square blocks – we’re doing the best we can with th people we have.”

Discussion then turned to a recent incident in which a person in crisis was throwing shopping carts into the street. Hughes said people from the shelter cleaned them up, and repeated, “Any neighborhood in Seattle has people with mental health issues on the streets.”

Another attendee asked who owns the building (“The West Seattle Veteran Center,” Hughes replied) and whether it had 24/7 security. “That would be $800 a day.” He mentioned “nine security cameras” that he and others watch.

The discussion grew increasingly contentious; one man who said he lives in the area said that, walking to the nearby YMCA, he’s seen “drug needles and foil, people passed out, half-naked men lying on the sidewalk” so he’s changed his walking route.

Another person: “It’s a challenging problem … can you point to a community anywhere in the United States that has solved this … I’m not denying it …it’s OUR problem … as a community… how are we going to solve it?”

One man suggested enforcement – of the law, of shelter rules – would help.

There were also suggestions to advocate with the Southwest Precinct, advocate with City Councilmember Rob Saka, and other officials (Hughes said “public officials” were all invited to the open house but none bothered to show up or even send a staff member).

A shelter volunteer observed, “Things will never get better until they have a sense of self-worth and self-dignity, a sense that somebody cares. The homeless today are like the lepers of Jesus – they are [considered] untouchable, unclean, all the ills of society are put on them.”

A nearby business owner requested “consistent communication” about the shelter and offered, “events like this are very helpful,” though another attendee said they’d been to a meeting back in February but “here we are in October and nothing is better.”

A shelter board member said the priorities still come down to the reason for the shelter: “There were 78 people here one night. Some of them might have (otherwise) frozen to death. I want laws enforced (too) but we’re ohe group trying to solve a problem” – saving lives.

Some suggested that perhaps the shelter could just serve people like the woman who told her story of helping out and then getting housing. The counter to that was that you can’t find people like that if you just put up a sign saying if you’re like her, you can come in.

Another nearby resident challenged Hughes to write, and carry out, “a neighborhood protection plan.” He said he’d write one if she wrote one. Shortly thereafter, he said again that funding is an issue and security guards cost a lot.

An attendee said that she understands mental illness because she has a child dealing with it, and “I’m all for helping people – it’s not that we don’t want to be compassionate but … teaching people that our community is hosting you here so you can’t steal from people, defecate in the doorway, use drugs.”

Hughes expressed frustration at the shelter seemingly being blamed for any and all problems in the surrounding area. “If something goes wrong, they call me.” Should he just close the shelter and let people freeze to death? he asked.

No conclusions or agreements emerged, but Utterback, in bringing the Q&A to a close, said the shelter board would discuss the situation at their meeting this week.

| 11 COMMENTS