Deb Achak is a West Seattle-based fine-art photographer. After living in various neighborhoods around the peninsula for almost two decades, in 2013 she and her husband bought and renovated the former Villa Heidelberg B&B along Erskine Way, where they now reside with their two sons, and where she works from her home photography studio. Last year Deb had her first solo fine-art photography exhibition in New York City, and also oversaw the publication of a new monograph: “All The Colors That I Am Inside.” West Seattle Blog senior contributor Christopher Boffoli recently sat down with Deb – who was fresh from travels in the Himalayas, where she was shooting her next project – to talk about how she came to photography, her connection to West Seattle, and the power of intuition.

(All images courtesy Deb Achak Photography)

(All images courtesy Deb Achak Photography)

By Christopher Boffoli

West Seattle Blog senior contributor

Deb Achak didn’t nurture childhood dreams of becoming a visual artist. She didn’t employ Malcolm Gladwell’s “10,000-hour rule” in pursuit of a life with a camera in her hands. In fact, you wouldn’t know from looking at the stunning, painterly fine-art images that she produces, that she came to photography fairly late in life, in what she has characterized as a “sudden and demanding compulsion.”

As someone who actually did start young, who has spent decades working at photography, and who still frequently fails at it, it’s hard to not be a bit envious. After all, we photographers can be a competitive lot. Observing Deb’s work often feels like eavesdropping on a conversation of someone particularly eloquent and perceptive. While photography may not have been in her early plans, some of the experiences of her childhood would inform the creative work that would come.

As a girl growing up in Amherst, New Hampshire, a creative career was the furthest thing from her mind. Neither of her parents were exceptionally creative. Both worked long hours supporting the family. There simply wasn’t anyone in her world who provided a blueprint for a career in the arts. Sometimes, though, life has a subtle way of illuminating things that we will circle back on later, even if we’re not initially conscious of it: like acorns that rain down around us, never knowing which ones will find purchase, seek out rays of sun, and later send up green shoots.

“My mother was a crafter. She was a quilter, “ says Deb. “She sewed clothes for us, did needlepoint, made stained glass. But we didn’t think of her as an artist. She worked as an HR director and she did these things at home.” Deb saw these endeavors as hobbies, apart from work life. “I figured you’d always have creative hobbies and then you’d have a real job.”

Deb’s childhood summers were a time of light. New Hampshire isn’t really known for its coastline, all 15 miles of it (18 miles by the most generous estimates). The state’s limited seashore is underwhelming as beaches go. But in the eyes of a child, it might as well have been the French Riviera. Like a lot of blue-collar families in the area, Deb’s spent time during their summers at Hampton Beach.

It’s perhaps not much different now than it was in the ’80s. One might not hear the same “woca-woca-woca” sound of Pac-Man spilling out of the arcades, but across the narrow ribbon of beach, and beyond the gray asphalt perpetually jammed with cars, you’re likely to find the same clam shacks and fried dough stands, T-shirt and souvenir shops, salt-water taffy vendors and people playing Skee-Ball. “We didn’t go to fancy beaches. That’s how we grew up. We didn’t have money.” Deb says that she mostly remembered it as “crowds of people relaxed and at ease, enjoying the ocean.” For what it lacked in luxury, it more than made up in sensory stimulation.

Later she would major in English at the University of New Hampshire, with an minor in studio art. But she claims the latter was more of a casual interest and never something that she imagined as a vocation. “I didn’t have any example of working artists. It wasn’t even on my radar.”

Like many who finished college at the end of the (first) Bush administration, a deep recession made for a challenging job market. Despite working multiple jobs, Deb just found she wasn’t surviving. “So I saved every penny and moved to the West Coast because a friend had moved here.”

Seeking adventure – and hopefully employment – Deb moved to Seattle in 1992. That version of the city would look largely unfamiliar to those moving here now. At the time, though, it seemed to suddenly be on the cultural radar of the world, in the midst of the white-hot success of the grunge music genre. Around this time, Starbucks had its IPO with around 165 total locations. AIDS deaths were still on the rise and Amazon was just a river in South America. Microsoft Windows was on its third version. “Sleepless in Seattle” was filming in town and Cameron Crowe‘s film “Singles” was screening in theaters. The Kingdome was still the city’s main sports and entertainment venue.

Deb couch-surfed with a friend for a while as she scrambled to work multiple jobs including waiting tables, staffing a catering company, and taking on cleaning jobs. At the same time she was diligent about sending out resumes and watching for openings. At length she found more promising prospects in a listing at Harborview, counseling victims at what was then called the sexual-assault center. She soondiscovered that she had a facility for the work, and found it fulfilling. This led her to similar work as a patient-care coordinator at a clinic at the University of Washington, where she liaised with physicians and nurses, helping with coordination between the medical side and law enforcement in pursuing sexual-assault cases. For a while she considered careers in law, or medicine, or mental health. But ultimately she chose social work, pursuing a master’s degree at UW.

Around the same time that she started working on her master’s, she met Ramin, the man who would become her husband. By the end of the ’90s, they decided it was time to buy a house, which led them to West Seattle. Over the next fifteen years they lived in several neighborhoods on the peninsula, during which time they became parents. Looking for something more spacious, they fell in love with the former Villa Heidelberg, which they bought (in 2013) and then spent years meticulously renovating. The exquisite result of that project has been featured in design magazines.

Deb’s transition from a challenging, if fulfilling, career in social work, into motherhood, and then into a multi-year house renovation project, progressively led her to picking up a camera. At first, she says, it was – like it is for a lot of parents – about documenting the childhood of her small children. But as much as she found cameraphones to be convenient, she quickly found herself chafing against the limits of the technology. “I just wanted something better to shoot with,” she says. After her husband gave her a compact Canon DSLR as a gift, her interest was supercharged. “I went everywhere with that camera. I really fell down the rabbit hole. I read the manual and taught myself everything that I possibly could.” Deb says that she set up an account on Flickr, which was very popular around that time, taught herself editing software, and joined every photo club she could find.

Soon after discovering this passion, Deb had an instinct to do something with a package of delicate optics and electronics that maybe wouldn’t be so intuitive to most: she wanted to submerge it in seawater. That risky decision fortunately would not end in disaster. In fact, it became the genesis of her first official series of elevated fine-art images.

“I bought an underwater housing because I wanted to photograph [her sons] in the water,” she says. But if Deb was perfectly fine with her new obsession, her sons very quickly lost patience for the process. “The initial water work happened because my kids got sick of me asking: ‘Could you do that again? … All right … A little bit more!’ They were like: We just want to play! And it was then that I realized that I was being a little too controlling. So I gave them some space and swam away from them out into the water, which is when I began to photograph what would become ‘Ebb and Flow‘.”

The series would be Deb’s exploration of the geometry of water, which dexterously portrays a sense of motion despite the frozen nature of still frames. While the waves above the surface flow into various corners of the frame, the lens often straddles both worlds above and below the surface, literally and figuratively. The images have dreamlike quality. It’s ocean waves: a universal perspective for anyone who has stood chest deep in rolling waves. But the images seem to take on something more, simultaneously looking above and below the surface of things, seeking abstractions in waves and bubbles.

This exploration of the aquatic very quickly led to a kind of oceanic street photography, as the subject of each frame incrementally began to feature more people among the waves. This follow-on series came to be called “The Aquatic Street.” One of the first images she shot for this series was a group of children (including her own) who were lining up so that they could climb up on some rocks and jump into the water. The water line splits the frame with a view above and below the water. The work quickly progressed from Deb taking in the wider scene to getting closer and more intimate portraits of people who essentially were doing the same thing that she and her family were doing: enjoying the water.

Street photography can be a challenging genre to do well. Besides the technical skills required to find compositions in spontaneous, dynamic situations, it also can require adept social skills, especially when approaching strangers (often foreigners) in a very media-wary age. And that doesn’t even begin to scratch the surface of other facets of ethics, culture, gender, etc. Though photographers can be inherently shy, often taking up photography specifically so that they can feel safe behind the buffer of a camera, Deb says that she prefers not to work that way.

The underwater housing for her camera is bulky. Sometimes she finds that this clear plastic housing doesn’t automatically read to people as a camera, so it can often invite inquiry. And once she has it set, she likes to hold it down in front of her chest. Or: “Over the heart,” she says, which is often at the water line, which captures an image split: above and below . “I always say that I’m curious about people under the surface. So isn’t it perfect that I stumbled into photographing people under the surface? Like, could it be any more literal?”

Again, she finds that photographing people at leisure is also key in being able to approach people with their guard down.

“I’m so curious about the inner workings of people. And that’s what I loved about my career as a social worker: sitting down and doing an assessment, figuring out their strengths, their needs, and how I can best serve them. And through this process you connect with someone really quickly, and you have to ask them a lot of questions, so you have to help them feel relaxed with you and trust you.”

While the seaside locations in her work are quite a bit more exotic than the Hampton Beach of her youth – Croatia, Italy, Iceland, Maui – Deb still sees a common human thread, regardless of the locale. “Across the board, if you’re swimming at the beach, you’re having a really nice time. And I started to realize like, oh, this is pretty universal. It took me a while to even realize that I’m completely referencing my childhood here. In all of these places there are quiet parts where you can go and be away from all of the people. But I’m always drawn to the loudest, most crowded spots of all.

“That’s the whole spirit behind this, not to embarrass someone in a bathing suit, but to show unabashed joy and actually how beautiful and poetic normal, regular bodies are in the water. Everyday people looking extraordinary, in my opinion. It’s actually also very personal and specific to the way I had fun with my mother and my siblings. And I came back to it as a mother because my boys loved it too.”

When asked about the potential discomfort of approaching strangers – camera forward – in foreign places, she says this is another place in which gender can be helpful. “Well, I’m a woman in my fifties, so I think that we’re often pretty much invisible. But I also have my kids nearby as decoys,” she adds with a laugh. “Just a mom shooting her kids with weird-looking gear that most people don’t know what it is.”

When the pandemic suddenly curtailed her ability to travel, Deb began to work more at home in West Seattle. The next two series, “Personal Space” and “My Eyes Need Beauty,” were more in the realm of still-life florals. Deb says that the isolation and restlessness she felt stuck at home, combined with stretches of oppressive wildfire smoke that blanketed the city in summer, compelled her to seek relief in the vibrant color and beauty of flowers. But even then, water remained a key element in her work.

She describes how she initially came to the images, setting up an elaborate portrait session that involved a subject, flowers, and a bathtub. She struggled with it but ultimately felt that it wasn’t working. “It was so over-thought and overwrought,” she says. And in the end all she had to show for it was a chaotic mess of flowers. However, she pivoted and it evolved to a new idea. Working adjacent to available light from large windows, in a narrow time of the day when the sun was just about to go down and the horizon was glowing, she agitated the flowers floating on the surface of the water and – hand-holding her camera – she was able to imbue a dreamlike sense of motion into the images.

This was not an easy process, with water splashing and flowers coming apart in the water. Enlisted family members helped to agitate the water as she worked. As she kept shooting, she was able to look past the initial stumbles of a new idea, finding the patience and vision to see through what wasn’t working, eventually discovering something in it. “I found myself curious about it,” she says, “And I started thinking of my camera as a paintbrush, with the flowers as the tubes of paint.” The result was a floral still-life series infused with a dreamlike sense of motion, and a fine-art series that would prove to be popular with local collectors.

By this time, Deb’s photographs had attracted the attention of local gallery Winston Wächter Fine Art, as well as its sister gallery in the heart of Manhattan’s Chelsea Arts District, which many consider to be the epicenter of the American fine-art world. The gallery had serendipitously become aware of Deb through a short film she had created at the studio of one of her friends, who also happened to be a painter the gallery represented. They liked the short film so much they asked if they could hire her to shoot one about another painter on their roster. And during that process they discovered Deb actually had her own fine-art photographs and encouraged her to show them some work. They agreed soon after to represent her.

Seattle gallery director Jessica Shea told me that the first series of Deb’s that they brought into the gallery was “Ebb and Flow,” but that Deb’s subsequent work has been just as much in demand with collectors. “What inspires me in all of her work is her ability to see the moments of beauty around us, every day. So much of her work is about being still in nature and appreciating how precious that can be. The ocean, a flower, a moment of stillness in someone close to her, all become reminders to all of us to value the world and the people around us.”

Deb would iterate further with florals (most sourced from a farm on Vashon island), adding black cloth as a backdrop, which would push the contrasts of color, all while maintaining the sense of fluid motion. It references the French Decadent movement, which rejected the notion that beauty is connected to perfection, and instead embraced the notion that things are more beautiful when they are on the cusp of decay, recognizing the fragile, transient nature of things.

As the cabin fever of the pandemic lifted, Deb’s horizons expanded into a new work called “All The Colors I Am Inside,” which, with an compendium of local landscapes and portraiture, expands upon her desire to seek out what lies beneath the surface of our interior lives. The images from the series would go on to comprise a collection that would appear at her first solo exhibition at Winston Wächter Fine Art in New York City in the summer of 2024, and also would be published in a gorgeously printed monograph, by Kehrer Verlag (printed in Heidelberg, Germany, an interesting coincidence given her home in the former Villa Heidelberg).

The forward of the book opens with a powerful anecdote about the death of Deb’s mother, and her deathbed mandate to “Trust your gut instincts,” words that Deb has said felt like they were “washing over her like stepping into a gentle stream.” And it is easy to see the urgency with which Deb assimilates this directive. Instinct and spontaneity are all over this work. And yet it is simultaneously thoughtful and carefully considered.

The origin of the word ‘instinct’ is close to impulsiveness. The painter Henri Matisse once wrote that instinct “must be thwarted just as one prunes the branches of a tree that it will grow better.” How many of us have had the experience of a sudden, unsettling feeling that something might be wrong – maybe before boarding a flight in stormy weather – worrying that some harm might befall us and superstitiously finding signs suggesting that maybe we should cancel, only then to land safely after a completely uneventful trip? Certainly we cannot respond to every whisper of intuition by conspiring with our own fear. But the way Deb funnels intuition into her work seems to suggest that she possesses no such trouble reconciling whether or not her instincts can be trusted.

The images are meditative and still, with bursts of lush color that brings richness and energy into the work. The hues are not assertive and garish, but muted and balanced by the softbox of overcast Western Washington skies. Whether the image is a path littered with dahlias, on the ground at the end of their life cycle, a muted moon seen through the silhouette of a stand of cedars, the remains of an expired Steller’s Jay in the grass, or a portrait in which a faceless subject enigmatically inhabits a frame, this archeological dig into the subconscious adroitly finds coherence and alignment.

The environment in which she works includes the local landscapes (streetscapes, parks, hiking trails) we inhabit every day; a world that is prosaic as it exists outside of her frame. And yet these places become elevated, taking on urgency as she suspends time, finding symmetry and balance in her compositions. With the authority of her camera, these moments and scenes slip into metaphor.

During most of Deb’s lifetime, photography was analog. And some of us can recall a time in the not-too-distant past when the act of photography was shrouded in the mystery of making photographs without instant gratification. Film would be saved – sometimes for weeks or months – until the roll could be finished and dropped off at the processing lab or Fotomat kiosk. Then one would return to pick up prints and would be surprised about forgotten moments, or just as often, disappointed about what didn’t come out.

As a contemporary photographer working in a digital medium, Deb obviously works in an era of privilege in which one can instantly see the results of what was shot. But due to the editing process, there still is quite a bit of delayed gratification before she is able to see her final fine-art images. Not only has she immersed herself in mastering many of the technical aspects of digital photography, but she extensively edits the images and prints them in her West Seattle studio, all of which requires her to draw from a separate well of expertise and patience as the raw images from the camera are cropped for composition, areas of light and dark adjusted, color intensified or muted, flaws removed.

Deb is quick to share the credit for this aspect of the work. For years now, she has worked closely with local retoucher Juan Aguilera, who helps her to distill the fine-art images from the raw material she has produced. “Sitting shoulder to shoulder with Juan has taught me so much,” she says. “There are all of the creative choices you make when you press the shutter. But I’ve found there are just as many creative choices with the post-processing as well.” Deb says that with this way of working, she’s very often not aware of what she’s captured until the end of the process.

With a successful first fine-art solo exhibition in New York City, and a well-received monograph in the recent rear-view mirror, it would be natural to ask Deb what comes next. Just as childhood summers informed her portrait work on beaches, and motherhood provided the imperative to advance her photography skills to photograph her sons, her next series of photographs continues to mine the quarry of childhood.

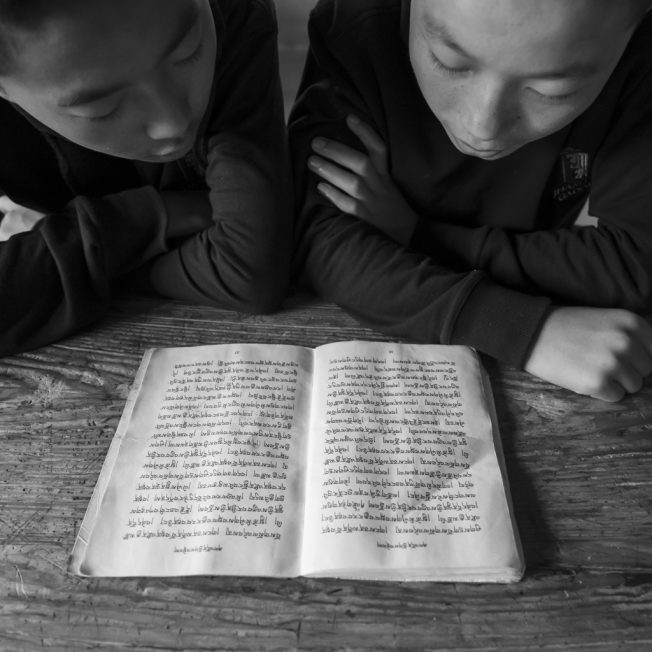

At the time I visited Deb’s studio for this interview, she had just returned from an adventurous journey into the foothills of the Himalayas, where she spent ten days photographing students who reside at the Jhamtse Gatsal Children’s Community, a home for orphaned and abandoned children located in northeastern India, along its mountainous border near Nepal. Founded by former Buddhist monk Lobsang Phuntsok, the school was the subject of a heartbreaking 2021 documentary, “Tashi and the Monk,” which is how Deb heard about it, and after which she felt a compulsion to make the trek to rural India. Traveling there with her friend (accomplished painter Tracy Rocca) the two were warmly welcomed to meet and interact with the students at the school, many of whom have endured neglect, abuse and bracing poverty. The result of the trip is a captivating new collection of work that Deb is diligently working to turn into her next book.

In the meantime, with one son at college out of state, and another still in high school here in West Seattle, Deb likely will continue to exercise her capacity for visual storytelling and her exploration of testing the quality of intuition via her imagery. The heart of this work seems to be informed by joy, whether it’s accessing the joy and ease of childhood summers long past, or the re-creation of this joy with her own sons during their summer holidays, or even in the people and landscapes of the common places we inhabit everyday. Deb adds, “These days, with so much pain in the world, joy seems like a welcome mandate.”

| 9 COMMENTS