(WSB photos. Drumming/singing at today’s event. At left, an image of Kikisoblu, Chief Sealth’s daughter)

(WSB photos. Drumming/singing at today’s event. At left, an image of Kikisoblu, Chief Sealth’s daughter)

By Tracy Record

West Seattle Blog editor

With this city named after its legendary leader, and home to a river bearing its name, the Duwamish Tribe says its lack of federal recognition makes no sense.

So the tribe is going to court, with a lawsuit launching a new chapter in the fight for recognition, which it says the federal government owes them as lead signatory to the 1855 Treaty of Point Elliott. The lawsuit – which you can read here – was announced during an hour-and-a-half midday event at the tribe’s Longhouse in West Seattle.

The event, attended by members and supporters via livestream as well as in person, featured Duwamish Tribe leaders as well as its lawyers, most of whom are with K&L Gates. The speeches, taken together, provided a history lesson as well as a briefing on the lawsuit itself (which also is laden with history). Here’s how it unfolded:

Duwamish Tribal Council member Ken Workman offered a message of welcome, in both Lushootseed and English. He spoke of Chief Seattle welcoming visitors almost two centuries ago.

Tribe counsel Aurora Martin talked about the “long journey” and said this announcement comes days after the tribe’s annual membership gathering. She mentioned the petition drive supporting recognition, launched a year ago. She said the new fight contains “a message of hope,” seeking “justice … long overdue.” Despite the lack of federal recognition, “the Duwamish Tribe has not ceased to exist.” The Interior Department’s “denial of recognition is incorrect,” she said. “Today has been a long time coming.”

Duwamish Tribe chair Cecile Hansen spoke about what Martin had called “the fight of a lifetime” in introducing her. She spoke of her ancestry (participants from the tribe named their family lineage in an around-the-room introduction; hers was Oliver). That fight, she said, dates back to the ’70s. (We even covered her direct confrontation of then-Interior Secretary Sally Jewell here in West Seattle in 2015.) She recalled her brother “getting cited for fishing in the Duwamish River” – to which the tribe should have had treaty rights, after signing the 1855 treaty: “We are still here.” She thanked supporters and vowed to “not give up.”

Speaking again in both languages, Workman returned to the podium to talk about the tribe’s history on the banks of the river across the street from the longhouse. “There were large houses here.” Speaking about the tribe’s role as environmental stewards, he evoked the significance of this time of year, alive with promise and freshness, relevant to the tribe again renewing its long-running fight.

Tribal Council member Desiree Fagan said she is from five generations of Duwamish women. She spoke of the limitations of being a non-recognized tribe, their lack of rights to display their own artwork. (We reported on a fight nine years ago over some art taken away from the tribe.) “I want my sons to experience Canoe Journey … to skipper and lead all tribes … I want my twin daughters to grow up knowing they came from the maternal tribe of Chief Seattle. … Our justice is long overdue.”

Tribal Council member James Rasmussen said he had followed family members onto the council, which was “reinvigorated” almost a century ago. He focused on honoring those who “have gone before.” He spoke of his decades of work with the Duwamish River – with the tribe as well as with the job from which he is about to retire, with the Duwamish River Community Coalition. That work has helped restore habitat for herons, for otters, for other wildlife, “more than any other place in the city of Seattle.” The river “is alive … just like we are. The recovery of the Duwamish River must include the restoration of the Duwamish Tribe.” He reminded everyone that the Clinton Administration recognized the Duwamish and Chinook tribes – and then that was taken away by the (GW) Bush Administration. “The Duwamish Tribe is owed reparations going back to that time.” The recognition is as much “about the people of Seattle” as about “the Duwamish people.”

Lupe Barnes from the Duwamish Tribal Services Board, also a former vice principal from Chief Sealth International High School, spoke too. She quoted the Rev, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

Then, about the lawsuit itself:

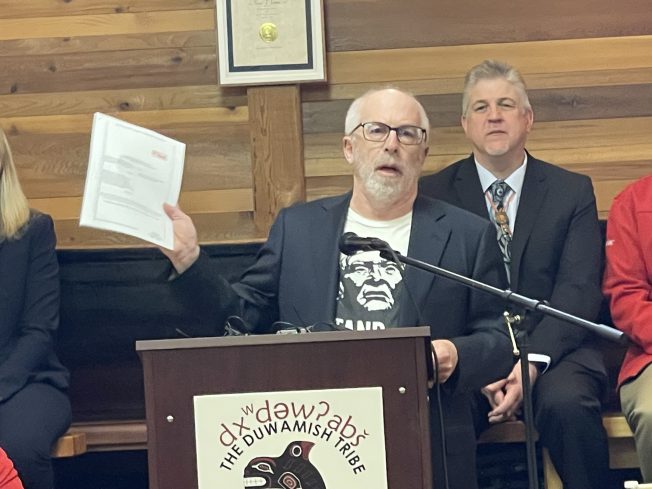

Bart Freedman of K&L Gates, the firm representing the tribe, spoke of three key points. He said the lawsuit was filed this morning in US District Court in Seattle. He noted that the Department of Interior’s actions rejecting the tribe’s recognition had been overturned previously – but that hadn’t led to recognition, so now they’re going about it another way. “We’re seeking to ask the court to directly recognize the tribe.” He said there is now precedent that “a promise made is a promise kept.” Congress ratified the Point Elliott Treaty in 1859 and that’s a “government to government recognition” – the Interior Department does not have the right to overturn that. They’re seeking to have courts recognize that. Back in 1925, the tribe was successful in a lawsuit, he noted. And the Department of Interior issued identity cards in the ’50s and ’60s to Duwamish people, he noted. “We’re going to ask the court to acknowledge this repeated and ongoing recognition.” Another key point: The U.S. has discriminated by failing to recognize lineage from Duwamish women who married non-Natives. Current tribe members are tied to five historic matriarchal clans, he noted – so denying recognition based on that, he said, is a Constitutional violation.

Tim Hobbs, also from the legal team, declared, “We are confident that justice will prevail.” He recounted their argument of all the ways in which there already was a relationship with the federal government – such as a 1934 court ruling recognizing the Duwamish as the historical tribe that signed the Point Elliott Treaty. Then came another commission’s recognition and a judgment “to compensate the tribe for the loss of its ancestral lands,” Then in 1966 there was a decision appropriating money to pay that judgment. “Denying formal recognition has been a grave injustice.” He contends that all the past recognitions mean only Congress could terminate recognition – and has not. “That is the end of the matter.” The Interior Department, he contended, does not have the authority.

Also from the legal team, Shelby Stoner: “So why won’t the Department recognize the Duwamish Tribe? … It takes issue with the ancestry,” she said, elaborating on Freedman’s point. The feds contend the women “somehow abandoned the tribe,” but, she declared, they did not. “This is discrimination based on sex.”

“The legal commitments made to tribes are commitments that need to be honored,” Freedman summarized. “We are literally standing across the street from a historic Duwamish village. The tribe is not able to hold the artifacts of its ancestors because it’s not recognized.” They had no access to federal health-care help during the pandemic. “The Department of Interior is on the wrong side of history.”

The event also featured speeches from supporters before a brief media-Q&A period. We asked about the ongoing PR campaign by the Muckleshoot, Puyallup, and Tulalip Tribes that have challenged the Duwamish Tribe’s legitimacy. Rasmussen replied with a direct message to members of those tribes: “Our fight is not with you – it’s with the federal government … it’s not about a big power grab at all … it’s about our rightful place.” He also urged the members of those tribes to “not listen to your lawyers … support us.” Freedman acknowledged that some other tribes have people of Duwamish ancestry “but that is fundamentally different from whether the Duwamish Tribe exists as a tribe that has a treaty relationship with the United States.” The government, he notes, has found that the Duwamish Tribe’s members are 99 percent descended from Duwamish people.

Asked what recognition would mean to the Duwamish, Rasmussen elaborated on the health-care denial, while Workman elaborated on the lack of access to the artifacts – which he said is “sacrilege.” He also mentioned a freedom to practice religion – being caught with an eagle feather for a non-recognized tribe’s ceremony, he said, could mean prosecution.

WHAT’S NEXT: Now that the lawsuit’s been filed, it will start making its way through the court system.

UPDATE: We recorded video of the Longhouse event; it’s added above as of 6:22 pm.

| 29 COMMENTS