Story and photos by Tracy Record

West Seattle Blog editor

It’s an almost-sacred trust: You turn or pull a handle to open a faucet in your home, and you expect clear, clean water to flow.

Unlike many areas of the world – as is being amply pointed out today, World Water Day – if you have lived here all or most of your life, it’s something you might not think twice about.

That’s why, for those who experienced “brown water” in recent months – as reported here repeatedly, starting when Myrtle Reservoir was offline for work but continuing intermittently even after it went back online – it was so startling, even when reassured that the water’s safe to use. Compounding the concerns is news from elsewhere, particularly the crisis in Flint, Michigan.

So that led some readers to ask, who’s routinely watching the water here, and how?

In response to that question, Seattle Public Utilities offered us a visit to its Water Quality Laboratory in SODO.

There, not only does SPU monitor and test samples from around its service area (the entire city and a few areas beyond) through a variety of lab procedures, it also convenes a twice-monthly gathering of taste testers. (To be precise – they test flavor, not taste. More on that shortly.)

Our visit was timed for that group’s most-recent meeting, but included a tour of the lab.

Our tour guide: Wylie Harper, who is SPU’s director of drinking-water quality.

As he put it, monitoring water quality is a 24/7/365 never-ending operation. More than two dozen people work on it – chemists, microbiologists, limnologists.

They test samples from locations all over the service area, shown on this map in a room at the lab:

The reservoirs and tanks in our area – West Seattle, Myrtle, Barton, Charlestown – are only a fraction of the samples they take regularly. Certain spots also tap right into the water system – “we’re sampling from what’s flowing in the street,” Harper explains.

You might have seen the SPU sampling “stands” and not even known what they were. Here’s one in North Admiral:

They sample in different pressure zones, to get a good representation. Here is the legend for what pressure is found where:

The samples are tested for microbes, coliform, chlorine, Ph, alkalinity, turbidity, and more. The federal Environmental Protection Agency has a list of what’s required, and “comes up with a new list” every five years. Five employees “spend most of their day driving to (sampling locations),” Harper says.

Two watersheds supply SPU – Cedar, and Tolt. Our water comes from the former, which, Harper points out, is 99.5 percent city-owned, and closed to public access. Its treatment plant is by Lake Youngs, a facility owned by SPU and operated by a contractor, CH2M Hill. Its water-quality levels are above what the state requires, according to Harper, and the contractor has financial incentives to keep it that way.

Storage facilities are visited at least every other week.

At the lab, many testing procedures are used – one that tints the water sample:

If it contains coliform bacteria, it would turn magenta, and that would lead to further testing. It could also lead to a boil order – immediate attention, as opposed to detection of metals, which “are cumulative,” Harper explained.

Sampling for metals such as lead and copper includes water collected from homes – voluntary participants – plumbed before 1980, when pipe standards changed.

Some aspects of testing are aesthetic; while we were there, they also were working on a test involving a type of six-inch PVC pipe “to see if any taste or odor” would result from the pipe.

Tests aren’t just to make sure there are no problems – they “drive how we run the system,” Harper said. (That happens from a different control facility nearby; the area of SODO where the lab is located is home to not only SPU facilities but other city properties including the facility holding the SPD evidence room.)

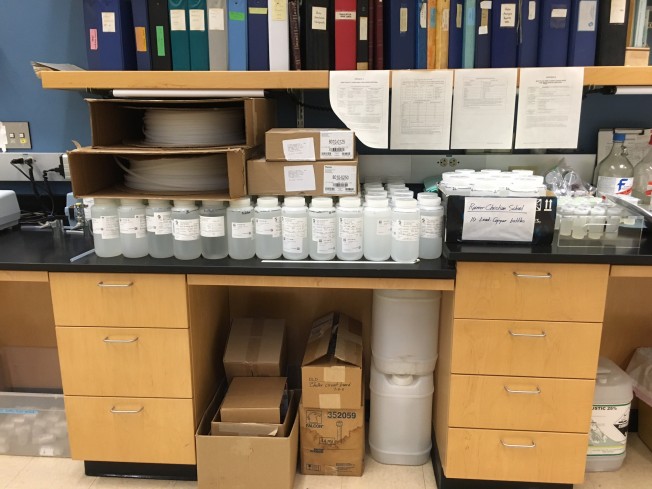

As our tour continued, we saw a variety of testing equipment, including equipment that superheats and atomizes water, to help analyze it.

Then it was on to the taste-test group (officially the Flavor Profile Panel), the latest participants in a program that SPU started more than 20 years ago.

The six panel participants are all SPU employees – from different parts of the department – who went through three months of weekly training sessions to qualify. Here’s some of what they sample for (also explained here):

They meet twice a month, tasting up to 12 samples, with two minutes inbetween. On the day we visited, they had nine samples. The water has been at room temperature for 48 hours before their sampling, and that releases the flavors – ones that even the most sensitive customers might not have noticed for some time.

Things have changed over the years, the panelists point out. Water from reservoirs each had distinct flavors when they were open (our area’s two reservoirs, Myrtle and West Seattle, were “buried” 5+ years ago), the testers told us. Reservoir-covering and changes in the treatment process have led to more uniformity.

The flavor-testing room is dedicated entirely to this process – nothing else happens there, so it’s kept free from odors that might interfere. (That includes visitors – we were warned against using fragrances.) The testers also have to refrain from other beverages, and food, for a specified period before their meeting. Their job is to assess odor and “mouthfeel” (such as “slick” or “tingly”) as well as flavor.

We take our leave as they wrap up their work and talk to Harper for a few more facts before our visit wraps up:

The system serves up an average of 120 million gallons for 1.4 million people on an average day; it serves more than two dozen wholesale customers too. That’s less than half what its reservoirs could provide – the Tolt’s daily limit is 120 million gallons, the Cedar, 180 million.

We asked about the wells near Sea-Tac Airport that were summoned into service last summer to augment the supply (part of what was blamed for one round of “brown water” here) – a situation that seems so long ago, on this side of our extra-rainy winter. They provided six or seven million gallons a day, Harper said. The well water is treated at the wellhead when it’s used – with chlorine, lime, and fluoride. (Yes, if you didn’t already know, Seattle’s water is fluoridated, the result of a referendum vote almost half a century ago.)

Before leaving, we asked Harper if there are any myths to debunk about Seattle’s drinking water. A few:

It doesn’t come from Puget Sound or Lake Washington – just those watersheds mentioned earlier. And, “For all the treatment we do, it’s not sterile.” But, it doesn’t have to be sterile to be safe, and that’s what the lab operations are designed to verify.

FIND OUT MORE: Besides some of the links we’ve included at relevant spots in this story, SPU has other resources online, including water-quality analyses and annual water-quality reports. And if you want an up-close-and-personal look at where your drinking water comes from, SPU offers seasonal tours.

| 7 COMMENTS